Advance HE asked staff working in HE institutions across the UK to complete a survey on their experiences and their wellbeing, at the point when the country started to open up again between October and December (before the second nationwide lockdown). This timing of the survey was planned to avoid the most restrictive policies, and to check in on staff working with increased flexibility, which many institutions are likely to take forward as official policy.

Flexible working, with more regular opportunities for remote working, if implemented well has the potential to allow staff to fit their work around their home life at a time and place that suits them. Many employees across industries have enjoyed the extra time they’ve gained through no longer commuting, and have reported increased productivity at home. There are of course many possible downsides to enforced remote working, but giving staff the choice of where and when they work is looking increasingly appealing to employers. This is new territory for the majority of universities, however, and staff must be properly supported to make the most of flexible or hybrid working.

Our survey asked UK HE staff to rate their satisfaction with their life, their job and their work-life balance, each on a scale from 1-10 while working from home. This has allowed us to compare the wellbeing scores of staff during this time with the general population pre- and post-pandemic, and with students.

Compared to the general population pre-pandemic, it does appear that staff wellbeing had taken a hit, even in the period when leisure and hospitality venues were starting to reopen. The Office for National Statistics estimated life satisfaction of the general population to be around 7.6-7.7 in the months just preceding the pandemic, and 7.2 in December 2020. Our survey showed that average life satisfaction of HE staff in October – December 2020 was similar to the general population, at 7.3.

However, when we dug deeper into the results, it became clear that the experience of staff differed considerably across types of jobs. Around 1 in 5 staff members (18.0%) reported low life satisfaction, 12.9% reported low job satisfaction, and just under a quarter of staff (23.9%) reported low satisfaction with their work-life balance. Academic staff, in particular, reported considerably lower wellbeing compared to professional and support staff. Their wellbeing was more comparable to students’, for whom the detrimental impacts of the pandemic have been well documented. The differences are particularly wide for staff satisfaction with work-life balance. In open-ended questions, staff told us of struggles with managing the extra workload required to deliver high-quality teaching and marking remotely on top of their usual research demands.

What can institutions do to support their staffs’ wellbeing in the move to more remote working?

What the data says

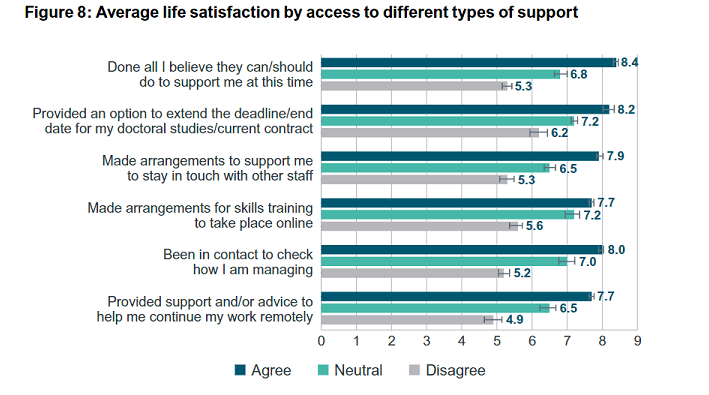

We also asked staff about actions their institution had taken to support them in the transition to home working. Across the board, staff who said their institution or department had supported them and provided them with the resources they needed to carry out their job remotely reported higher satisfaction with their life, their job, and their work-life balance. This highlights the importance of pastoral care of staff for supporting their overall wellbeing.

What staff want

However, it would not be realistic to expect that the list of response options we offered in the survey could cover all of the possible ways institutions could support their staff. So we asked staff directly: Is there one thing your employer could do or have done differently to help improve your experience of transitioning to remote working? Over 1,000 staff members provided considered and detailed responses to this question.

Around one in five respondents only had positive things to say or said that there was nothing more their institution could have done, and many acknowledged the difficulty of the situation for their institution. However, a large number of staff members reported real difficulties in the transition to remote working, and a fundamental lack of support from their institution.

The main things staff felt their institution could do better were:

- Provide (better) equipment and practical resources

- Improve senior leadership’s response and decision-making

- Reduce, or properly acknowledge, increased workloads

- Line managers, and other staff, could check-in with them more regularly, or at all

- Improve and tailor institution-wide communications

Results from analysis of each theme, and what is covered under the broad headings, can be found in the full report.

While teething problems during such a monumental change in working practices, with little notice, would be expected, some of the themes and comments stood out to us as issues that could, and should, be dealt with as quickly as possible.

In particular, we were struck by the number of staff who said that no one had checked in on them since the beginning of the pandemic, or simply requested that they had more contact with their manager/ team (theme 4). The comments below reveal the experiences of just some of the staff who felt isolated or ‘left behind.’

“I would like more sustained support, no one has checked in since early in April to see whether our working from home needs have changed, and I don’t know where to look for further support.”

“Some regular 1-1s from immediate line manager as have to request these so feel am ‘bothering’ them. Team catch ups are about work and cannot discuss private matters here. I feel as a manager they should be regularly ‘checking in’ with all staff in their team from a workload and mental health/wellbeing perspective. Do feel a little left to ‘get on with it’.”

“I feel like we have just been left to get on with it, and we need regular checks on how we are. All we get are emails with links to read, but what’s missing is the personal 1:1 support. Regular catch-ups with line manager/researchers. I feel quite isolated and at times like people wouldn’t notice if I wasn’t working.”

Some responses were from managers, who discussed difficulties balancing the additional pressures of an increased workload as well as increased need to support the wellbeing of their direct reports, with little or no access to additional support or training themselves.

These findings were mirrored in the quantitative results. While staff who said someone at the institution had checked to see if they were managing had an average life satisfaction score of 8.0, those who said no one had checked in on them had an average score of just 5.2. Whether or not a lack of contact caused lower wellbeing among these staff members, it is clear that staff who were not checked in on were the ones who needed contact the most.

Where to go from here?

Our survey revealed very different experiences across staff members, and these are partly reflected in the different approaches institutions took to supporting staff. We have put forward a number of recommendations institutions could take forward to help staff to make the most of flexible and remote working. Some of these can be put in place immediately and require limited resource, for example:

- Provide training for managers and leaders at all levels to support them in effectively managing remote working teams. This should help to ensure good communication, awareness of wellbeing issues and, in turn, staff productivity.

- Formalise open and frequent conversations between employees and line managers to monitor staff members’ wellbeing, including working hours to avoid overworking.

- Gather information about your staff’s wellbeing and support requirements that are specific to your institution. Anonymous feedback mechanisms, (eg pulse surveys) can be a useful tool for identifying issues as they arise. Where possible, include demographic questions to understand the impact on different groups of staff.

- Where staff/peer networks and groups are in existence, ensure these are appropriately resourced and supported, with the work recognised and rewarded as appropriate.

Where institutions intend to retain some of the new ways of working, and move to a more flexible approach, we have also made several recommendations that will take longer to implement, and will require monitoring and updating.

Our results have signalled the power positive workplace policies and practices can have on staff wellbeing, both in their life and in their job.

About the author – Dr Natasha Codiroli Mcmaster is a quantitative researcher at AdvanceHE and is experienced in using large-scale longitudinal survey data to explore social phenomena. At AdvanceHE she works primarily with HESA data to understand the experiences of students and staff in Higher Education (HE), with a particular focus on equality, diversity and inclusion. Her recent work includes a report detailing differences in student’s participation and attainment in HE according to their religion and belief. Natasha holds a PhD in quantitative social research from the Institute of Education, UCL. Her research focused on the relationship between student choices in Higher Education, their graduate outcomes, and their ethnicity, gender and social background.

Before joining Advance HE, Natasha worked as an analyst in the civil service and most recently helped to shape the research agenda for a new charity supporting civil society in London, London Plus.

This blog is kindly repurposed from AdvanceHE and you can read the original here: How have HE staff fared during the pandemic?