“Are your colleagues bugging you? It could be a good thing in building a resilient teaching team”…in the fourth in the series of blogs and events exploring ‘Developing sustainable resilience in higher education’ – our member benefit theme for September 2020 – Dr Kay Hack, Advance HE Principal Adviser (Learning and Teaching), explores collective resilience.

A single fire ant will struggle in water, whereas a group can float effortlessly for days (1).

Surviving since the early Cretaceous period and with over 10,000 species, ants are regarded as one of the most resilient species on earth today. They have adapted to occupy most terrestrial eco-systems and, through the diverse roles they undertake, they have a huge impact on other species and an important role in sustaining the environment.

Resilience in this evolutionary context includes the speciation of ants to adapt to new environments over millions of years as well as the ability of an individual colony to adapt to new opportunities and threats in real time, aligning with the American Psychological Association definition of resilience as “The process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress” (Building your Resilience, 2012), that has been used to underpin this blog series.

In previous blogs, Cindy Vallance and Claire Pavitt highlighted the contentious nature of the term ‘resilience’; and the implicit assumption that we should all be able to ‘bounce-forward’ -when not everyone has a trampoline. This blog will explore whether the collective responsibility of a collaborative team can protect against the risk factors associated with an uncertain future and considers whether collective resilience is an emergent property of a collaborative team that might alleviate the emphasis upon individual resilience.

Changes to the Higher Education landscape have necessitated closer collaboration across teaching teams. Contextual demands of quality assurance, larger cohorts and flexible and distributed delivery models as well as student and employer calls for more integrated, competency based curriculum have driven the need for a collaborative approach in teaching teams. The pedagogical benefits derived from a holistic and collaborative approach to curriculum design and delivery are well-established. The lone academic who ‘drops in’ to deliver a series of lectures on their pet topic without reference to their colleagues or the students prior or co-current learning is an increasingly rare species in a teaching team. Are there additional emergent benefits that can be derived from collaborative working? What aspects of team collaboration are needed to provide the social safety-net that ensures all members of the team can thrive, rather than survival of the fittest?

Why are ants so successful?

Success is attributed to two well-established elements of ant behaviour- co-operative working and communication, allowing an ant colony to complete complex tasks beyond the capabilities of any one individual.

In social science terms an ant colony would be considered to be a an entitative group, a single entity distinct from its members, with shared goals and responsibilities and a common fate. The degree of collaboration within teaching teams lies on a spectrum from a loose aggregate of individuals towards team entitativity. Unlike many teams in businesses or organisations (or ant colonies) teaching teams can operate both within and across boundaries – schools, research groups, professional services and faculties. Individual team members may have discipline, administration, research, leadership and other roles and responsibilities beyond the teaching team. Lessons and understanding drawn from research on highly entitative teams are therefore not always applicable to teaching teams. If we want to leverage the benefits associated with closer collaboration in order to develop a model of team resilience to support all team members we need to understand the factors that contribute to team cohesion and those that can disrupt it.

All members of the colony understand what they need to do for the colony to survive and thrive and have a shared ownership of the outcomes.

A resilient team needs a collective sense of purpose. Agreeing that student success is the primary purpose of the teaching team makes it easier for individuals to identify the tasks they need to undertake to accomplish that goal. As discussed earlier, members of teaching teams will have conflicting goals which need to be acknowledged and accommodated openly to ensure distributive justice, avoiding frustration and accusations of social loafing.

The ability to quickly gain and retain information allows ants to rapidly switch tasks as the needs arise, providing the colony with agility and adaptability.

Trusted and open communication amongst team members can provide indispensable peer support as teams operate in this new environment. As well as sharing best practice peer review and other practical support, it is vital that we invest in building relationships and goodwill through meaningful conversations. This can be as quick and simple as sending a message to a colleague. “I saw this article and I thought it would be of interest to you” tells me that a) you are thinking of me and b) you have an appreciation of my work and my interests. Providing a social-safety net for colleagues supports the growth of all individuals thereby allowing the team to flourish.

Worker ants select the roles they undertake shaped by preference and aptitude and informed by feedback and success.

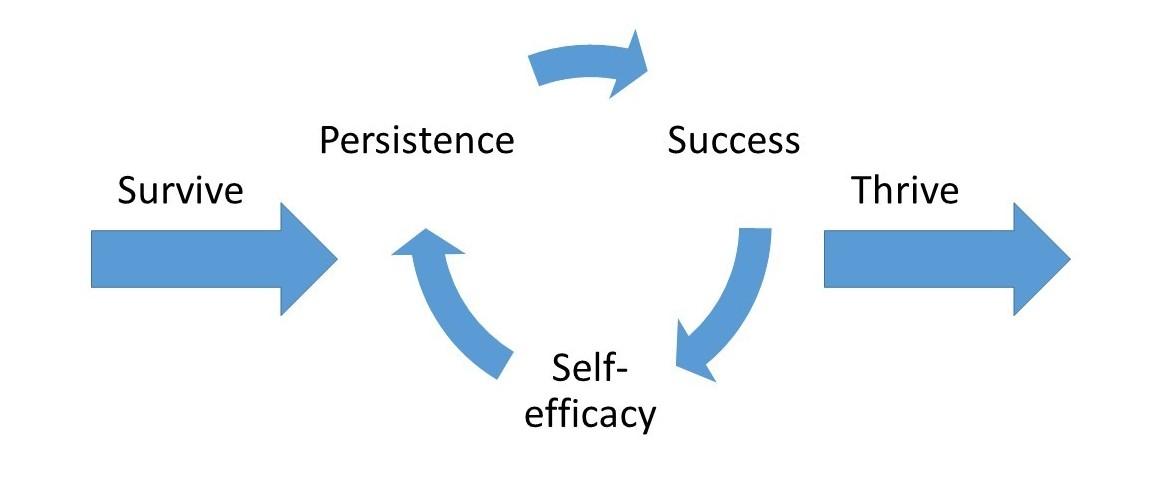

Success is a driver for promoting self-efficacy and persistence. This virtuous circle is driven by positive feedback from peers, line managers and students, the vicarious pleasure derived from motivated and engaged students undertaking meaningful activities, and the reward that comes from having a positive impact on the learning of others. But do we give sufficient recognition to all the roles that contribute to this success? How do we support colleagues who feel they are ‘failing’ at a task? Are our relationships sufficiently open and trusted that we can ask for help?

Dr Hala Mansour tweeted “The face of a supervisor when your student smash it in the viva #proudsupervisor”

Soon and Prabhakaran (2) described team resilience as “a team’s capacity for positive adaptation which refers to a team’s collective potential to innovate and change to meet the demands of a difficult or novel situation” , this collective efficacy is reliant on the team’s belief and ability to cope with the change (3).

This belief in its own ability is driven by trust, from peers, students and the organisation. Too often we see team resilience being disrupted by changes in organisational structures, policies and strategies, or a lack of distributive justice, without discussion with the ‘worker ants’ who are doing the heavy lifting. Associate Professor Nicholas Freestone (Higher Education Bioscience Teacher of the Year, 2014) recently noted on Twitter, that the most passionate teachers circumvent university policy and procedures to do what is best for their students, concluding:

“We’re the experts, we got the degrees in our discipline, we need the confidence to do what we know best”

The prevalence and persistence of ants indicates the importance of communication, collaboration and a collective sense of purpose to establish a resilient team, but where does the responsibility lie for establishing the conditions for resilience to develop? The individual, the team, the leadership or the organisation? In next week’s blog, Kim Ansell will explore this further in considering how trust, transparency and inclusivity is critical to promoting resilience throughout the organisation.

- Mlot, N. J., Tovey, C. A., & Hu, D. L. (2011). Fire ants self-assemble into waterproof rafts to survive floods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(19), 7669-7673

- Soon, S., & Prabhakaran, S. (2016). Team resilience: An exploratory study on the qualities that enable resilience in teams. Singapore: Civil Service College.

- Bandura, A. (2010). Self‐efficacy. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology, 1-3.

Author:

Dr Kay Hack, Advance HE Principal Adviser (Learning and Teaching), explores collective resilience.

This blog is kindly repurposed from AdvanceHE and you can find the original here: The art of the resilient teaching team.